Taking Notes in Ecological Field Work

Some Recommended Practices

There are some differences between those who would always take a Field Journal into the field for direct recording and those who have a pocket notebook for their Field Notebook which they later expand, transcribe, and elaborate in a larger format Field Journal.

Among issues to consider in this decision are the disposition of original sketches in your field notebook (how would these be transferred into field journal) as well as personal time issues – will the researcher (you) have time and take the time to perform the second step of expanding the notes into a journal. You might practice and experiment with both methods and develop your own unique hybrid approach that works best for you. The goal in either case is to have a practice you will engage reliably that produces the fullest, most complete, accurate and original documentation of your field observations and data.

Field Notebook and/or Journal –

(Field Notebook example above from Michael Canfield’s Field Notes on Science and Nature, Harvard University Press, 2011)

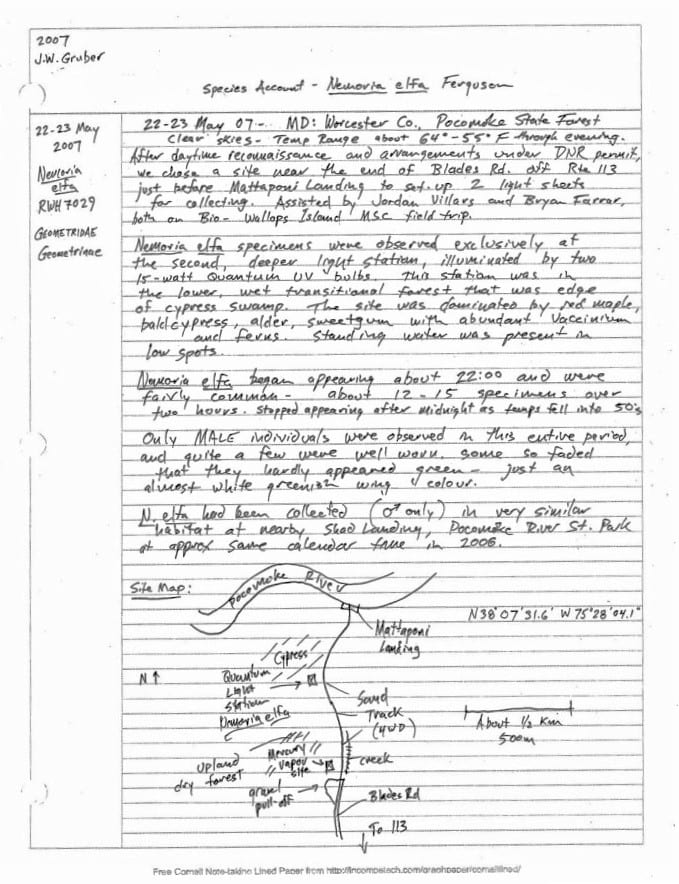

This document is organized chronologically by date and site visited for field study. It provides a running sequence of field activity in time order across the year.

The journal holds “raw” data from the field in real time. It should always include the site location, conditions, direct observations, and can also record impressions, thoughts, or impulses. Hours (time of day), other members of field party present, lat-long GPS waypoints and/or coordinates with elevation are included. Habitat description goes here with geographical and/or geological summaries, different types of plants present, dominant vegetation, wetness or dryness (recent rains, standing water, prolonged drought, etc).

Collecting activity – details of light sheets, sweeping, beating, netting, etc. Summary account of the species assemblage observed and collected. At this point, many insect species collected are likely to be undetermined or very tentatively and partially determined (best guess in the field), It makes more sense to describe the individual specimens of note with a general group i.d. instead of putting down a definitive species name that may turn out to be wrong and therefore misleading to others later who read the notes.

Example:

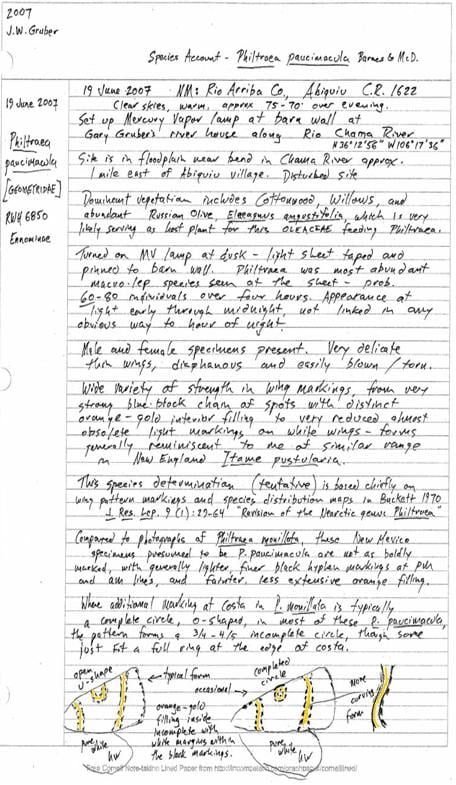

“Abundant (40 – 50 individuals over two hours) delicate white geometrid moth with blue black chain of hyphen marks at am and pm lines, outlining a light orange-gold central transverse line. (poss.

Philtraea sp.?)”

Could record approximate numbers of individual species over time (15 individuals over three hours) or a general description of relative abundance: abundant, common, uncommon, rare or single-specimen.

Behaviors, time of appearance for a night flying insect at light, and any mating activity are all useful things to watch for and record.

Associations of a specimen (beetle, wasp, fly etc) with a specific plant or flower is useful as is any observed feeding behavior (nectaring behaviors, any predation). When beating foliage for insect adults or lep larvae (caterpillars), it is very useful to get the plant identity (or even a pressed sample of the plant material) to associate the plant with specimens. It is also worth noting in the field book when a photograph is taken, with the digital image reference number if possible (example, “Photographed cerambycid beetle on yellow aster flower at this site, IMG6345-712”).

Sketches and drawings here could include quick maps, sketches of the landscape, sketches of plants, sketches of individual specimens or a noteworthy detail of a specimen (antennae form, wing patterns, etc).

The journal is also a great place to note ideas, connections, questions, and follow-up suggestions or plans for further investigation.

Field journal or notebook can also accompany researcher to collections when visiting collections for study at museums, universities, or individuals’ personal collections. Here it is especially valuable to note what specimens are present in the collection, any apparent misidentifications, interesting variations or unusual forms, any type specimens present, and important label data that documents collecting data (date and location) for species of interest.

Species Accounts –

These are more detailed, elaborated pages that are commonly organized taxonomically, and as such are often useful if they are on looseleaf paper in a binder within a given year so there can be shuffling and reorganization / reordering of pages as species are added. After the complete year’s species account pages have been assembled, the looseleaf pages could be inexpensively bound in a hardcover volume. In these pages, information can be elaborated on specific species that have been confidently determined. Working from the field notes and the specimen, data and relevant observations and ideas can be developed for one particular species. Since it is species-indexed, these accounts can sequentially list multiple sites and dates where one particular species was seen and/or collected. In this way it draws together all the information and observations for one particular species over a year’s time in one place (even if it’s just a one or two line entry saying the species was seen or collected on a given date/location). For an example of a species, account, see page illustration below.

Catalog –

The catalog is a numerical indexing document valuable to anyone who keeps a collection of specimens that might be referenced in the future. The catalogue listing assigns a catalog number to each individual specimen, and then lists important collection information so that the specimen can be cross-referenced with notes in the species accounts and field journals. The catalog number can then be associated with the actual physical specimen with a pinned label or tag. Each entry should include the label data on collection locality and date. The catalog entries can also contain physical specimen data – condition, sex, measurements/size, and other useful specimen data. Because it is numerical, sequential, and typically assembled back in the lab or office, the catalog is a good candidate for an electronic format, and might even be constructed as a searchable database. Any additional studies that have been done (DNA extraction, dissection or genitalic preparations, or photography) could also be noted and referenced in the catalog listing.

- Species Accounts

Two examples just below.

A Species Account page for Philtraea paucimacula, a Geometrid moth collected in New Mexico in June, 2007:

Collecting species account for Nemoria elfa